Regulatory framework

3.1

The fires in the Grenfell Tower, and other high-rise buildings in

Australia and internationally, linked to flammable external building cladding

highlight a wide range of issues surrounding non-conforming and non-compliant building

products.

3.2

This chapter examines a range of matters that have aggravated the issues

of non-compliance and non-conformity in building products in Australia such as,

product importation, reports of fraudulent certification and the risks

associated with product substitution. The chapter discusses some of the

proposed measures to address both the use of non-complaint and non-conforming

building products more broadly. In particular, it looks at measures to address

the use of Aluminium Composite Panels (ACPs) with polyethylene (PE) cores which

have been identified as a major fire safety risk in modern buildings.

Aluminium Composite Panels

3.3

The fires in the Lacrosse and Grenfell buildings, as well as similar

fires in Dubai and China, have all involved ACPs, made of highly combustible PE

Aluminium Composite Material (ACM).

3.4

This type of panelling consists of two thin aluminium sheets bonded to a

non-aluminium core, and are most frequently used for decorative external

cladding or facades of buildings, and signage. They are classified as

attachments in Australia and New Zealand, and it is a requirement of the

Building Codes in both countries that the panels, 'irrespective of their fire

classification', only be attached to fire rated walls. Such panels must demonstrate

that they will not contribute to the spread of flame in the event of fire.[1]

3.5

ACPs are manufactured with various cores ranging from a highly combustible

PE core up to the non-combustible Aluminium honeycomb core. It is important to

note that there is a difference in price and weight between the flammable PE

cored material and the fire retardant and fire-proof cored material.[2]

3.6

The Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) noted that ACP cladding is not

the only external wall components that could be dangerous if used in a

non-compliant manner. As such the National Construction Code (NCC) 'takes a

blanket approach to all external wall components, including assemblies (or

systems) to reduce the spread of fire within and between buildings'.[3]

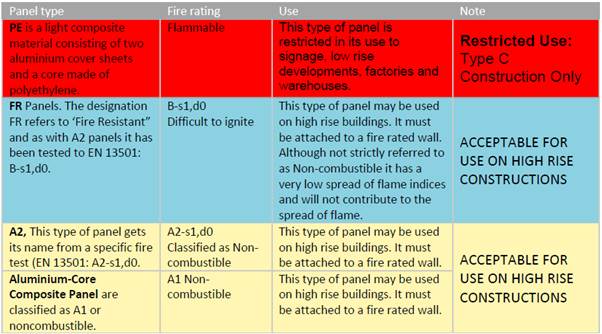

3.7

The table below explains the types of ACPs available and details their

uses.[4]

Table 1: Type of

Aluminium Composite Panels and their uses

3.8

The ABCB made the following observations in relation to the

combustibility of external walls:

-

With the exception of low-rise buildings (typically single storey

residential buildings and two storey commercial, industrial and public

buildings) and single dwellings, the NCC requires that external walls must be

non-combustible if using a Deemed to Satisfy Solution. In this context, the NCC

contains some concessions whereby, provided specified conditions are met, a

multi-residential building of up to four storeys may be permitted to have

combustible external walls.

-

Non-combustibility of a material is determined by testing to

Australian Standard AS 1530.1. The NCC also lists some low hazard combustible

materials that can be used where a non-combustible material is required (such

as fibre-cement sheeting).

-

The NCC Deemed-to-Satisfy Provisions also require that any

attachments to the external wall must not impair the fire performance of the

external wall or create an undue fire risk to the building's occupants as a

result of fire spread or compromising fire exits. Permitted attachments are

generally incidental in nature such as a sign, sunscreen, blind, awning, gutter

or downpipe.

-

If not following the Deemed-to-Satisfy compliance pathway, a

Performance Solution for combustibility of external walls must be able to

demonstrate that it will avoid the spread of fire in and between buildings,

including providing protection from the spread of fire to allow sufficient time

for evacuation.[5]

Increase in the number of products being imported from overseas

3.9

Since the 1990s, there has been a significant decline in Australia's

manufacturing base. The effect of this decline has been a transition where the

majority of products used in the Australian domestic building market are now

imported from overseas.[6]

The prime risk identified with the importation of construction materials into

Australia is the difficulty in establishing if the materials are compliant with

the relevant Australian standards.

3.10

Certification of a product indicates that it is compliant with a

mandatory standard like the Australian Standards or a voluntary third party

certification scheme (like the CodeMark), which confirms that a required

standard has been met. For certification to be effective a standard must be

clear, information about the standard should be easily accessible, monitoring

and auditing of material against the standard must be maintained and consumers

must have confidence in the credibility and integrity of the certification

system whether it is onshore or offshore. Furthermore, enforcement, including

penalties for non-compliance, need to be maintained.

3.11

In its submission to the inquiry, the Australian Institute of Architects

noted the 'enormous array of materials coming from international

manufacturers'. It flagged the concern that the certification credentials of

imported products are not always reliable. It noted that at this point in time,

'any person can import construction products and materials, and many of these

would not understand the Australian Standards relating to the materials they

import. Nor would many understand the implications of using the material

inappropriately'.[7]

Reliability of certification documentation

3.12

The committee heard of numerous incidents where individuals and

businesses believed that import materials compliance documentation was possibly

suspect. Fraudulent or misleading product certification documentation enables

non-compliant or non-conforming materials to be easily used or substituted on

Australian building sites. For example, the Australian Institute of Building

Surveyors (AIBS) stated that they had identified 'incorrect, fraudulent or

inadequate documentation and certificates of adequacy' as one of the potential

reasons 'why non-compliant external wall cladding has been installed on so many

buildings in Australia over the past 30 years'.[8]

3.13

Mr Travis Wacey, national Policy Research Officer from the Construction,

Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) also raised similar concerns about

the prevalence of the use of fraudulent certification. Mr Wacey considered the

issue to be widespread and provided an example of the types of fraudulent

certification that has been found by the CFMEU:

The example is that we find something that is stamped as a

certain product or comes with certain paperwork, certain certificates, saying

something along the lines that this is compliant with a certain standard and

has been certified under this testing regime by this testing authority, and

subsequently someone makes an inquiry with that testing authority and it is

found that the test never occurred; they have never heard of this distributor

or manufacturer.[9]

3.14

Mr Wacey also highlighted the limited number of prosecutions in relation

to fraudulent certification. He was aware of examples where false or misleading

statements claiming conformity with a standard had been raised with the

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. However, he understood the

'examples might not have been prosecuted with reference to the list of

priorities in terms of the agency'.[10]

3.15

Mr Murray Smith, Acting Chief Executive Officer, Victorian Building

Authority (VBA), highlighted a recent case which had been prosecuted by

Consumer Affairs Victoria involving a false certificate for a fire safety or

separation wall—a product designed to prevent or delay the spread of fire.[11]

3.16

Many in the industry told the committee that they felt that the problem

of fraudulent documentation was significant, Mr Rodger Hills, Executive

Officer, Building Products Innovation Council (BPIC), considered it was a

'massive problem within the industry'. Mr Hills noted that one of BPIC's

members, the Australian Windows Association had 'literally thousands of

documents that are fraudulent'.[12]

3.17

Mr Hills observed that in his experience:

A large part of it—I won't say all of it—is from imported

products. The imported products, for whatever reason, can be tested to varying

standards and not necessarily the standards that people think. The

documentation could be completely fraudulent, with no testing done at all.

There has been forging of NATA [National Association of Testing Authorities,

Australia] certificates and forging of industry code certificates and things

like that. It gets very difficult then for a building certifier or an engineer

who is trying to check...If you look at the asbestos contamination in the Perth

hospital, the builder had all of the proper information and all of what they

believed to be relevant certification documentation, which turned out not to be

correct.[13]

3.18

Likewise the Australian Institute of Architects submitted

that 'fraudulent documents abound', noting that architects had reported that

'relying on the supplier/agent to supply the appropriate information and

documentation can be difficult'. In its view:

To avoid fraudulent documentation, it appears that the only

avenue for a higher degree of certainty is to request third party product

certification. However, for the construction industry, the current patchwork

system of assessment schemes is unwieldy. There is great disparity amongst the

schemes as to the quality of assessment, level of auditing and checking for

fraudulent documentation.[14]

The risks associated with product substitution

3.19

Along with deliberate misleading or fraudulent documentation or

certification, non-compliance and non-conformity can be demonstrated through

product substitution. When a similar, often inferior and, generally cheaper

product is substituted it has the significant potential to underperform when

compared to the original product specifications. Product substitution has been

identified as perhaps the most significant contributing factor to the prevalence

of non-compliant external cladding materials on Australian buildings.

3.20

Mr John Thorpe, Chief Executive Officer of CertMark International, noted

that since the Lacrosse fire in 2014, his company has examined high-rise

properties where the body corporate provided the building plans which

specifically state that fire-retardant material was to be used and there has

been a substitution for a PE. In CertMark International's experience:

Substitution occurs, from our perspective, when a builder, or

somebody in involved in the purchasing process, is looking to save money.

Basically, what's happened is there's been a tender go out for the building, a

company's won the tender and the first thing that happens is they look to find

savings.[15]

3.21

Icon Plastics cautioned that product substitution was a 'major problem

within the construction industry'. Of particular concern was:

...the continued substitution of compliant products in favour

of lower cost non-compliant products and systems. This unfortunately is done

mainly through the construction phase of the project. Either building companies

or installers will substitute products to make the project more profitable for

themselves.[16]

Concerns about the National Construction Code

3.22

Ignis Solutions told the committee that it considered the complexity and

lack of clarity in the National Construction Code (NCC), to be a primary factor

leading to the use of flammable cladding materials.[17]

3.23

The ABCB is a joint initiative of all levels of government in Australia.

As such, the Board is a Council of Australian Government (COAG) codes and

standards writing body that is responsible for the development and maintenance

of the NCC, which comprises the Building Code of Australia (BCA) and the

Plumbing Code of Australia (PCA). While the ABCB submission notes that it 'aims

to establish minimum performance based and proportional codes, standards and

regulatory systems that are consistent, as far as practicable, between states

and territories', Mr Neil Savery, General Manager of the ABCB, emphasised

that 'the ABCB is not a statutory authority; it has no regulatory powers, no

powers of compliance'.[18]

These responsibilities lie with the relevant state and territory authorities.

3.24

As outlined, the code governing the built environment in Australia is

the NCC. The NCC is a performance-based code, meaning there is no obligation to

adopt any particular material, component, design factor or construction method.

The Performance Requirements for the construction of all buildings can be met

using either a Performance Solution (Alternative Solution), which can be done

in consultation with the state and territory planning and design authorities or

using a Deemed-to-Satisfy (DTS) Solution:

A Performance Solution is unique for each individual

situation. These solutions are often flexible in achieving the outcomes and

encouraging innovative design and technology use. A Performance Solution

directly addresses the Performance Requirements by using one or more of the

Assessment Methods available in the NCC.

A Deemed-to-Satisfy Solution follows a set recipe of what,

when and how to do something. It uses the Deemed-to-Satisfy Solutions from the

NCC, which include materials, components, design factors, and construction

methods that, if used, are deemed to meet the Performance Requirements.[19]

3.25

Prior to the introduction of the performance-based codes, building codes

were very prescriptive, as Mr Norman Faifer, Immediate Past National President,

Australian Institute of Building noted:

Before the Building Code of Australia was in, we had only one

regime, and that was prescriptive, highly specified, in the book. If it was not

in the book, it did not get a look. In order to provide innovation and

inventiveness and allow some latitude to architectural design and construction

techniques, we went to performance based. Opening the door to performance based

product and solutions then opened up the regime of who certifies, who says that

this is an approved method or product to use, under the performance based.[20]

3.26

The Warren Centre for Advanced Engineering observed that the 'greater

use of performance-based design appears to be threatened by inadequate

regulatory and administrative weaknesses and a lack of attention to

practitioner competence'. At the same time, it also considered that

performance-based codes had provided many benefits to the building and

construction industry, such as innovative buildings and cost effective

construction projects.[21]

3.27

Ai Group recommended that the evidence of suitability provision in the

NCC be reviewed as they felt that the provisions are too broad. It suggested

rewriting the provisions to:

-

differentiate between the varying levels of assurance (i.e. third

party certification is more credible than self-declaration) and the types of

building materials and systems that should align with these levels of

assurance; and

-

differentiate between material conformance and design

conformance.[22]

3.28

The AIBS, while supportive of the Code, maintained that the NCC needs to

be revised to 'remove ambiguity of interpretation and provide greater clarity

around the evidence of suitability provisions supporting performance based

design and assessment'.[23]

The AIBS also expressed its support for the BMF's resolution to improve

industry wide understanding of the performance assessment process available

within the NCC, noting:

Building surveyors are often frustrated by the lack of

understanding of the evidence of suitability requirements and performance

assessment processes among design consultants and believe a widespread

mandatory education program on these aspects of performance design is required

to address the issue.[24]

3.29

In relation to the code's effectiveness regarding flame retardant

products, Mr Graham Attwood, Director of Expanded Polystyrene Australia,

considered that there were loopholes in the NCC, that need to be 'tightened up'

to ensure only flame retardant products are used in building and construction. [25]

Mr Attwood stated:

There are loopholes in the Australian standards, and there

are loopholes in the NCC, the National Construction Code, that allow certain

product lines to fall into play. That may or may not be a conscious decision,

but, in the whole building process, once an approval is given to construct a

domestic or commercial building, the next stage on is to look at ways to

minimise cost in the construction phase. Sometimes loopholes are found to

actually implement and move away from this, while still supposedly compliant

with the broad element of documentary compliance; however, the specific and

detailed areas of, for instance, applying certain Australian standards to this

particular code have got flaws and have got holes in them that need to be tightened

up.[26]

3.30

Furthermore, the AIBS provided a number of examples to emphasise its

concerns about the lack of clarity in the NCC including the concern that

'Specification C1.1 Clause 2.4 [in the NCC] has been identified as providing

for some degree of use of combustible elements on parts of building facades'.[27]

3.31

The committee heard that performance-based pathways can enable a

collective arrangement of adaptations, suggested by builders, such as

additional sprinklers or fire walls to circumvent more prescriptive elements of

the NCC. Ignis Solutions stated that the NCC currently has a performance-based pathway

which permits the use of PE core ACPs in high rise buildings above the

prescribed floor height limit for such panels. Additionally, Ignis Solutions

also raised concerns in relation to wall fire safety compliance, stating that 'the

NCC is fragmented, confusing, lacking in definitions, contradictory with

conflicting prescriptive clauses and has no hierarchy between the conflicting

prescriptive clauses'.[28]

3.32

Mr Benjamin Hughes-Brown, Managing Director of Ignis Solutions

explained:

[The NCC] is contradictory, with no hierarchy of control for

various clauses which compete with each other. The matter of fire safety and

building compliance is too great to rely on one person. By way of example,

let's take sarking used for external walls for weatherproofing. One part of the

code requires it to have a flammability of less than five. This indicates that

combustibility is permitted. Another part of the code says that the external

wall must be non-combustible. How is this to apply for a consecutive nature? If

it is used externally, does the clause that allows it to be used as combustible

apply internally? Well, you don't put sarking on internal aspects of a

building. And does it apply to only low-rise type C construction? There are no

requirements for fire resistance in many applications for that. So what does

the flammability requirement actually hold on that front? The Australian

Building Codes Board has written a nine-page document to provide clarification

on these two levels of clauses. A nine-page document to provide clarification

certainly highlights that something is not right.[29]

3.33

Ms Liza Carroll, Director-General, Queensland Department of Housing and

Public Works, noted that the introduction in Queensland of a performance-based building

code in 1996 informed the Queensland Government's decision to examine those buildings

that were constructed between 1994 and 2004 as the initial scope for its cladding

audit. Ms Carroll noted:

I think this goes to the kind of thing that happens within

the Building Code, as I am sure you are aware, which is: is it non-flammable,

non-combustible cladding or is it a performance solution so it can effectively

replicate the standards that might be required? So there is a focus on: do some

of these buildings have performance solutions and were they appropriately

tested back then.[30]

3.34

In addressing these and other concerns raised about the effectiveness of

the NCC, Mr Savery of the ABCB stated that 'the performance based code is a highly

sophisticated regulation and it needs properly qualified and trained individual

assessors in order to understand how a performance based code works'. He

observed:

In the early 1990s, we introduced a performance based code

which is highly sophisticated regulation; it is not something that the average

individual can necessarily understand. You need qualified, trained people to

understand how a performance based code works. At the same time as that,

private certification was incrementally introduced around the country. At the

same time as that, we had a process around the country of deregulation or

reduction in regulatory requirements around things like mandatory inspections.

At the same time as all of that is happening, the world is changing around us.

We have global supply chains. We have multinational companies operating. [31]

3.35

Mr Savery, having agreed with the committee on a number of statements

regarding the lack of compliance in the system and the erosion of confidence

through the gradual removal of elements such as mandatory inspections, also

noted that there is considerable non-compliance occurring in the industry.

There is noncompliance occurring. We have got non-compliant

products, but I would suggest to you that it does not end at non-compliant

cladding.

...

Not just products; non-compliant construction. It is not just

a product; the actual potential construction of a building[32]

3.36

Mr Savery was asked 'who was responsible for the existence of these

unsafe buildings' and whether they were a product of deregulation. Further, the

committee asked Mr Savery if he believed the answer was to reregulate. Mr

Savery informed the committee that these particular question was being considered

by the BMF's expert review into the Assessment of the Effectiveness of

Compliance and Enforcement Systems for the Building and Construction Industry

across Australia.[33]

3.37

Mr Hills from the Building Products Innovation Council (BPIC) believed

the industry support a move to reregulation including 'nationally consistent

approaches to training, licensing and banning of non-complying products and

buildings'.[34]

Committee view

3.38

The committee notes the concern from witnesses and submitters that the

non-compliant use of cladding is widespread and that there have been extensive

delays in developing and implementing policies to address non-compliance and

non-conformity in the building industry.

3.39

As highlighted in Chapter 2, the committee notes that the BMF has now

released the Assessment of the Effectiveness of Compliance and Enforcement

Systems for the Building and Construction Industry across Australia review's

terms of reference and its timeline. The committee looks forward to following

this review and learning about its outcomes.

3.40

The committee also welcomes the recent announcement that the NCC would

be amended to reflect the ABCB's new comprehensive package of measures for fire

safety in high rise buildings. The committee is hopeful that this amendment to

the NCC, if delivered in a timely manner, will provide greater clarity and

reduce the ambiguity around interpretation which has been identified by stakeholders.

3.41

Of particular concern to the committee, and stakeholders, is the long

time lag between government responses to the Lacrosse fire in 2014 and any

meaningful resolution between governments, the BMF, and the SOG on possible steps

forward. Furthermore, the committee notes that more disastrous fires have

occurred internationally, but Australia has yet to implement any major reforms

or communicate any course of action publically. Considering the prevalence of

PE core cladding across Australia, the committee considers it paramount that all

governments focus attention on this issue before the next disaster occurs.

Need for greater clarity of CodeMark Certificates of Conformity

3.42

The need for confidence in the conformity of Australian building

products is paramount. Certificates of Conformity issued under the ABCB's

voluntary CodeMark Scheme are evidence that a building material or method of

design fulfils specific requirements of the NCC. Currently, there are a number

of external wall products on the market displaying a CodeMark Certificate of

Conformity, including some aluminium composite panels.[35]

3.43

Icon Plastics highlighted the importance of clear product labelling in

reducing the incidence of product substitution. It considered:

One quite simple way of stopping this type of practice is to

have all products labelled with the appropriate standards and certificate

number, the particular product has passed. All products would then be able to

be visually checked as they arrive on construction sites, prior to

installation. This would also be confirmed with copies of the test certificates

either supplied by the manufacturer or the importer.[36]

3.44

Mr Murray Smith, the VBA, drew the committee's attention to two critical

weaknesses in the current building product certification system which were

highlighted by the Lacrosse building fire:

...firstly, that there is no single organisation or regulator

responsible for certifying products for compliance with relevant standards and,

secondly, that, certificates of conformity with the Building Code of Australia

performance requirements, where available, are not always explicit in respect

of the range of uses and circumstances in which a product may be relied upon to

be fit for purpose.[37]

3.45

Mr Savery of the ABCB advised the committee that the CodeMark Scheme had

been overhauled. Mr Savery also explained that there had already been a review

in train prior to the Lacrosse fire which was then expedited further noting:

One of the key changes has been the introduction of a new

certificate. It was deemed by the board that the existing certificate did not

adequately describe to the practitioner what the limitations of the product

were or what performance requirements of the code it satisfied. So the new

certificates which have been road tested by the conformity assessment

bodies—they are the bodies that issue the certificates—are more precise in

terms of describing what the product complies with. A product will not comply

with every requirement of the code; they will only be seeking to attest to

certain parts of the code and what the actual limitations are in respect of

that product.[38]

Mandatory third party certification, national register and product auditing

3.46

The committee notes that the SOG report included recommendations to assess

the costs and benefits of mandating third party certification and establishing

a national register for high risk products (see paragraph 2.44).

3.47

Mr John Thorpe, Chief Executive Officer of CertMark International argued

that the quickest way to address the use of high risk products would be to make

the CodeMark Scheme mandatory, stating that 'I'm not saying everything needs a

mandatory certification—decorative items that are non-flammable, obviously

not—but that could be a move that could go ahead quite quickly'.[39]

3.48

The Australian Institute of Architects also considered third party

product certification to be only avenue to avoid fraudulent documentation and

provide a higher degree of certainty. However, in its view, the 'current

patchwork system of assessment is unwieldy. There is great disparity amongst

the schemes as to the quality of assessment, level of auditing and checking for

fraudulent documentation'. It also noted:

Third party certification from a testing laboratory that is

properly recognised and accredited by NATA is essential, as is current

certification schemes, and product registers coming under the one umbrella to

ensure that minimum standards are upheld. The certification and testing regime

should not be limited to imported products, but should apply to those

manufacturers in Australia to ensure that all products comply

with Australian standards.[40]

3.49

AIBS advocated for random testing and auditing as well as developing a

central product register:

An ongoing and proactive system of random auditing and

testing of high risk products undertaken by the testing bodies should be

introduced, with significant penalties for those found to be involved in the

supply or manufacture of non-conforming products. Once a product has been found

to be compliant, all testing details and evidence of suitability should be made

available via a central body responsible for the coordination and publication

of that information, to ensure that the latest information is readily

accessible to all involved in the design and assessment processes.[41]

Committee view

3.50

Submitters and witnesses have raised concerns about the progress of the

SOG Report's recommendations, which were due to be finalised in May 2017. The

committee is concerned that progress appears to have stalled and there is no

clearly identified timetable for implementation. The committee is of the view

that the implementation plan should be released as soon as possible to assure

stakeholders that progress is being made and again makes its point about the

timeliness in response to these issues.

Proposal to ban aluminium composite panels with a polyethylene core

3.51

Many who provided evidence to the committee believed that the complexity

of the NCC and the ability to undertake 'Alternative Solutions' to items that

would appear to most people to be non-negotiable, led them to advocate for a

total ban of the highly flammable ACPs with a Polyethylene (PE) core in

Australia.

3.52

The committee heard from three distributors of ACM panels during the

inquiry. Two of the companies—SGI Architectural and Fairfax

Architectural—supported a ban on PE core ACPs.

3.53

Mr Clint Gavin, National Sales Manager advised the committee that SGI

Architectural fully supported a national ban on the importation of PE core

ACPs. He noted that SGI Architectural had made a conscious decision in 1999 not

to import PE core products, and are now only importing fire retardant products

with a fire retardant non-combustible mineral filled composite core. Mr Gavin said

that his decision was made despite the fact that SGI Architectural had lost

business to companies who provide the cheaper PE core products. [42]

3.54

Fairview also supported a ban of PE core ACPs due to the risk that they

can 'inadvertently be substituted for the correct product'. Fairview indicated

that it had ceased manufacturing PE core ACPs two years ago, although its

remaining PE core stocks may still be sold if requested. Fairview advised the

committee that it would write off its remaining stocks if a ban was issued.[43]

3.55

Mr Bruce Rayment, Chief Executive Officer of Halifax Vogel Group,

cautioned against a blanket ban as PE core ACPs are also widely used in the signage

industry. Mr Raymont noted that the company was not able to confirm where

its products had ended up, or whether they were used in a compliant manner.[44]

3.56

Mr Thorpe, CertMark International, did not believe there was strong

argument for being able to have a niche market for flammable products in the

building industry. He concluded that 'the simplest way with PE flammable core

materials, as with any flammable material that is in a building, is it should

be banned; it should be kept out of the marketplace'.[45]

3.57

Mr Smith from the VBA observed that banning PE core ACPs would 'make

regulation a lot simpler'.[46]

3.58

Similarly, Ignis Solutions submitted that there were 'no legitimate uses

for PE core materials in Australian buildings be it cladding or signage, that

cannot be cost and life safety effective with a fire retardant core panel'. [47]

3.59

The committee was advised that there was not a significant price

difference between PE core and fire retardant panels, particularly in light of

the potential cost of millions of dollars for remediation of buildings found to

be clad in PE core ACPs. The committee was informed that the price of a panel

is approximately $50 per square metre. Mr Rayment of Halifax Vogel Group advised

that 'for us the difference in price between the polyethylene cored material

and the fire-resistant material, at a wholesale price, is A$3 a square metre'.[48]

3.60

However, the CFMEU acknowledged the complexities surrounding the

introduction of an import ban while there are still compliant uses of PE core ACPs.[49]

The committee also notes that Australian Border Force has previously advised

that it is not in a position to reliably determine whether an imported building

product will be used or installed correctly.[50]

3.61

Despite this complexity, the CFMEU suggested that if necessary, the

Australian Government could introduce interim import bans on the product 'until

systems were established to provide the public with confidence that products of

this type were going to be used appropriately and compliantly only'.[51]

The CFMEU considered that such an action would be consistent with Australia's

international obligations as the World Trade Organisation's Agreement on

Technical Barriers to Trade states:

No country should be prevented from taking measures necessary

to ensure the quality of its exports, or for the protection of human, animal or

plant life or health, of the environment, or for the prevention of deceptive

practices, at the levels it considers appropriate.[52]

3.62

The Hon John Rau MP, Deputy Premier of South Australia stated:

We have the capacity, if there is completely unsafe building

material—whether it be cladding or something else—at risk of coming into the

country, to stop it at the border. Once it's in, once it's past the port and

it's into the distribution network, chasing it, catching it and identifying it,

particularly after it's been used, is an absolutely massive task and one for

which, quite frankly, as far as I'm aware, nobody is adequately resourced. When

I say 'nobody' I mean any level of government. So the obvious answer, it would

seem to me, is to find effective mechanisms to root this material out at the

point of entry into the country to the extent that we possibly can.[53]

Committee view

3.63

The committee understands that under the NCC in its current form, there

are compliant uses for PE core ACPs in low-rise buildings, as well as pathways

through performance-based solutions to allow the use of PE core ACPs in

high-rise buildings. The committee also understands that the signage industry

uses PE core ACPs.

3.64

In light of the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy, the committee does not

consider there to be any legitimate use of PE core ACPs on any building type.

The committee believes that as there are safe non-flammable and fire retardant

alternatives available there is no place for PE core ACPs in the Australian

market. While Australian Border Force and suppliers of ACM are currently unable

to determine whether an imported building product will be used in a compliant

manner, the committee believes a ban on importation should be placed on all PE core ACPs. In addition,

the sale and use of PE core ACPs should be banned domestically.

Recommendation 1

3.65

The committee recommends the Australian government implement a total ban

on the importation, sale and use of Polyethylene core aluminium composite

panels as a matter of urgency.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page